Case Study A: Merimetsa-Stroomi

>>>back to working groups overview

Rationale

Merimetsa / Stroomi is an area in the northern district of Tallinn, characterized by a biodiversity to be preserved, different types of landscapes and different uses. From the sea to the city, there are the sandy beach of Stroomi, an urban park and a forest characterized by a protected area, which at the moment is limited in the heart of the same, but within 2027 it should be extended. Each of them is destined for different uses, there are: bathing beach, play areas for children, areas equipped for grilling in the park, paths through the woods in the protected area and an hippodrome on the eastern border of the forest. All these parts are connected by two driveways in the northern and southern borders and by small natural trails, which give the area a suggestive character and at the same time don't give disabled people the possibility of easy access. Furthermore, a natural feature connects the areas, the swamp, which with the subsidence degrades the forest and the park.

Location and scope

A Landscape System Analysis

A.1 Landscape layers and their system context

Geomorphology, landscape units and coastal typology

The shore is covered by a wide sandy area composed of fine sand and silt deposits, which descends gradually to a very flat sandy foreshore. There are some 2 – 3 m high dunes in the forested backshore. A discontinuous punctual urban development is taking place behind the dunes. Studies reveal an unsatisfactory ecological condition of the water due to the high nutrient content and accompanying eutrophication.

The area is subject to various physical processes, leading mainly to accute erosion. Wave activity and the wind-induced surge during storm events are the principal drivers oferosion in the study area. Other agents such as ice, and the decline os sediments in the coast add on to the vulnerability of the shore.

Land use

During the last three decades, the green urban areas to the east and the wetlands to the southwest remained the same, while the semi-natural landscape near the shoreline and in the south (park-forest Merimets and Stroomi beach) was partially urbanised. The surrounding buildings are mainly industrial but some areas tend to gentrify. The surrounding areas in the north urbanised much more quickly than the area of Merimetsa. However as we can see, the surrounding areas in the north urbanised much more quickly than the area of Merimetsa.

Merimetsa/Stroomi is one of the last vast semi-natural area east of Kopli Laht bay and is likely to remain the same. This can be explained by 2 factors linked together. First, being at the low end of the bay, Merimetsa area is suitable for sediment deposition resulting in beach and dune formation (the Stroomi beach being an example of this phenomenon). Therefore and since the 19th century, the practice was to reforest these areas to prevent any sand progression into the inlands. The second linked factor is that these areas are not often suited for agricultural purpose and therefore have no use for soil exploitation. The swamps of this low height coastal landscape can be a reason why no urban development has started yet.

Green/blue infrastructure

The major potential elements of a green/blue infrastructure network are:

- the sea with the costal shore (Stroomi beach)

- the Stroomi park

- the urban forest

- the swamp

- hippodrome

- pollinator corridor

The Stroomi beach is a public place and one of the most popular beaches around Tallin. The water is very flat but still suitable for swimming.

There are:

- several playgrounds,

- a big trampoline,

- ball playground,

- a surf school/ shop,

- changing cabins,

- an outdoor fitness area,

- 2 outdoor cafes and ice cream sale,

- an official nature trail.

Besides you can rent sun loungers and pedal cars. In the swimming season there is a coast guard. The Hippodrome in the neighborhood is connected with Merimetsa as the horse racing cars drive through the flat water at the Stroomi beach from time to time. The Stroomi Park is a very popular barbecue and picnic area.

The accessability could be improved, but a basic construct is available: there is wheelchair & prams access, public transport ((busline 3, 40, and 48) and access by car (parking area) from each side oft the area. It would be nice to improve wheelchair and prams access for the forest (some paved roads) & the beach (some wooden terraces on the sand). In any case, the area is easily accessible for many people and is highly frequented, especially during the summertime. There are a lot of wild barbecue fires in the forest, which is very dangerous especially when the wood is dry in summer. This may result in a loss of a high quality piece of nature inside the city, in case of a big forest fire. In the future it will be a challenge to find balance between preservation of nature and human activity at Merimetsa-Stroomi.

In the summer of 2018, there were difficulties with cyanobacteria at the Stroomi beach. Caused by the climate change, they covered huge areas on the sea with blue-green foam. Swimming was not recommended due to toxins that can irritate skin and eyes or cause nausea. It will be a problem for such a popular beach as the Stroomi breach if this happens every year. This problem has to be solved in a larger context, not only by the Tallin municipality itself.

When put in a larger context, it is important to note that the green infrastructure in Tallin is fragmented and many areas act as an individual island. In the future it will be a challenge to connect them well. An official nature trail goes through the Merimetsa area and is already well connected with the Süsta Park. It will be important to connect the individual green islands with each other on different levels, for example by a busline as well as by walking trails.

Actors and stakeholders

- Merimetsa/Stroomi coastal area is part of Tallinn municipality, which is divided into 8 districts. Merimetsa/Stroomi belonging to Põhja-Tallinn district. Each district has its own government that fulfills the functions assigned to them by Tallinn legislation and statutes. The changes in the landscape are mostly driven by them. The 48 hectares big nature reserve on the project area is ruled by the Ministry of Environment and owned by the State Forest Management Centre (RMK). The surrounding area has a lot of apartments, so for a lot of people it’s the nearest green space available. There are a lot of local people whose life quality the surrounding area affects a lot. Right now local people are the ones that are the most affected by the changes, but they have the least power to actually make them. One way for local people to have a more powerful voice in the future is that they could collaborate with a non-profit organisation called Linnalabor who would help them improve urban space according to their wishes.

Sacred spaces and heritage

Merimetsa park is the most prominent heritage site of the Merimetsa-Stroomi focus area. Originating as the backdrop for the home of the local noble family, the park has served to connect the Seewald mental hospital to the Stroomi beach since the early 20th century. It is of value to the patients, local community, and people from the wider area of Tallinn alike. It is under nature conservation.

A local noble family donated its summer manor and land to an Estonian mental health association in the late 19th century. On its grounds rose one of the most modern psychiatric hospitals of Europe in 1903. It may therefore be the most widely recognized heritage site in the Merimetsa-Stroomi area, its significance to medical workers extending beyond the borders of Estonia. The name "Merimetsa" actually comes from the german word "Seewald", which was the name of the summer manor.

Visual appearance and landscape narrative

- The landscape of Merimetsa-Stroomi park and seashore has characteristic features with its sandy beach, and its park with the protected area.

Many Painters illustrated the interesting natural landscape, the colorful sea, and the nice trees in the natural park. Paul Burman depicted "Stroomi" 1888-1934, where trees show on the hill.

- Story of Merimetsa-Stroomi:. Stroomi Beach Park is equipped with benches, trash bins and barbeque spots, as well as walking and cycling paths, numerous playgrounds, sporting and training facilities. The beach building, life-boat station, beach facilities rental and public catering facilities are also located within the park area. The name Stroomi originates from the name of the owner of Stroomi pub previously located near Paldiski Road − Mr Bengt Fromhold Strohm − once there existed a road leading from the pub to the beach. Yet, it has another name as well − Merimetsa wood − which originates from Merimetsa summer manor which used to be near Paldiski Road. One of the first images of this area can be found on the map of 1688 by Samuel Waxelberg, where the region is depicted mostly as a grassland. There must have been natural trees and bushes as well. The dampness of the area taken into consideration, willow groves and birch stands (on the higher and drier spots) must have existed

A.2 Summary of you landscape system analysis and your development Targets

In this area, the growing urbanization because of the population increase is a driving force. Nevertheless, here there are also pressures as climate change and swampy soil that cause land subsidence. In this zone, there is the Merimetsa protected area: it is very important for people living in the area around it, offering opportunities for picking mushrooms and berries and practicing recreational sports. The area is popular with athletes, dog owners and riders. It is also possible to promote nature education in the protected area and encourage research. For these reasons, many different associations are interested to preserve it: they are a driving force. The visit load of the protected area is high and reached a critical tolerance limit in certain areas. Although the protected area has lighted paths and it is surrounded on three sides by pedestrian light traffic routes, visitors have also created a number of smaller tracks. This has damaged the soil, destroyed vegetation and reduced biodiversity. Larger damage is in the northern corner and in the central part of the protected area, where are illuminated trails, barbecue sites and exercise grounds (volleyball court, so-called outdoor gyms, children's climbing wall, etc.). In open areas, illegal campfire sites were also found, which might increase the risk of fire during the dry season. For all these reasons, the insufficiency of infrastructures and the unsupervised activities are pressures. There are the sandy beach, and children's playgrounds near the protected area that attract lot of people in beautiful weather. In fact, the tourism is another driving force of this area. However, it has a direct impact on forest communities as the littering increases, also because of the lack of accommodating structures and no supervision of these activities. There are same possible responses to this status quo in order to reduce the pressures and the impacts. First, it is important to realize interventions on swampy zone, and then to plan all area: built quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure as new connections between the different parts to integrate the several activities. In this way, provide access to safe, inclusive and accessible, green and public spaces, in particular for women and children, older persons and persons with disabilities. In fact, the area needs preserve its multifunctionality and improve tourism through the building of accommodation sustainable structures and green infrastructures. Moreover, develop and implement tools to monitor sustainable development impacts for sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products. The planning should ensure the conservation, restoration and sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, in particular the forest and wetlands; promote the implementation of sustainable management of forest, and restore it where is degraded.

Sustainable Development Goals at risk

- Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure.

Basic infrastructure like roads, information and communication technologies, electrical power and water remains scarce. This goal is at risk in this area because there are few infrastructures: there are not many throw in the forest; a lot of them realized without an urban plan or a project by the government.

- Goal 11: Make cities inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable.

Rapid urbanization is exerting pressure on fresh water supplies, sewage, the living environment, and public health. Recently the popularity of this area raised, this zone attracts more local people and tourists but it causes loss of natural heritage because of insufficient infrastructures.

- Goal 12: Ensure sustainable consumption.

Humankind is polluting water in sea faster than nature can recycle and purify and excessive use of water contributes to the global water stress. In this area, this goal is at risk because the sandy beach attractes many tourists and local people that cause pollution with their waste.

- Goal 13: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

Global emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) have increased by almost 50 per cent since 1990. From 1880 to 2012, average global temperature increased by 0.85°C. Oceans have warmed, the amounts of snow and ice have diminished and sea level has risen. This goal is at risk in this area because the growing urbanization and the realization of possible future unsustainable infrastructures will increase in global average temperature.

- Goal 15: Sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, halt biodiversity loss.

Forests cover 30.7 per cent of the Earth’s surface and, in addition to providing food security and shelter, they are key to combating climate change, protecting biodiversity. In the urban forest there is the Merimetsa protected area, where are illegal campfires and grilled zones that increase the risk of fire and deforestation. Moreover, the visiting pressure has damaged the soil and destroyed vegetation.

Hypothesis

Both the absent interventions on the marshy area, and the increase of uncontrolled activities, such as those of the Ippodrom, sports and bathing, could damage the natural zone of Merimetsa. It could happen not only because of them but also because of the growth of the city around the forest, which is not all included in the protected area.

- active plans/plans in activation phase :Merimetsa protected area management plan 2018-2027 ,

A.3 Theory reflection

- International policy document

At the international level and since 2015, the International Guideline on Urban and Territorial Planning is one of the main documents of the United Nations listing key principles and recommendations for any stakeholders aiming to develop a territory. These recommendations are categorised into 4 domains: policy & governance, social development, economic growth and environment. All these domains follow 2 constant rules: promote economic growth in a sustainable manner and ensure inclusion of all groups, especially socially vulnerable ones during planning processes.

The Environmental section of the international guidelines is as matter of fact of high relevance concerning Merimetsa area, an area being a mixed of semi-natural landscape, wetlands and urban green zones. Regarding the recommendations, the document emphasizes on the necessity to keep and protect these natural habitats/ecosystems and their biodiversity in order to mitigate impacts on climate changes. It also values the cultural dimension of such places, in the purpose of proposing an improved quality of life in urban or rural areas. Therefore and according to this document, Merimetsa area should preserve its natural aspect and even strengthen its natural resilience as a leverage for the city of Tallinn to adapt its shoreline to global warming.

- European policy document

European Landscape Convention, Florence 2000; signed by Estonia in 2017 and ratified in 2018. This Convention applies to the entire territory of the Parties and covers natural, rural, urban and peri-urban areas because the quality and diversity of European landscapes constitute a common resource. It includes land, inland water and marine areas. It concerns landscapes that might be considered outstanding as well as every day or degraded landscapes. The aims of this Convention are to promote landscape protection, management and planning, and to organise European co-operation on landscape issues.

- National policy document

National policy document “Tallinna arengukava 2018-2023” is divided into six main strategy fields, each with its own goals. The main goals that have been set and that also affect our area are the following:

- For tourism: to promote Tallinn as a popular location for city break.

- For the population: to encourage national minorities to experience and take part in cultures other than their own. According to the population register, the population off our project area is ethnically diverse.

- For new development: to bring sea into the public urban space by developing residential areas by the sea.

- For green structure: sustainable use of natural resources and creating a unified green structure.

A.4 References

- https://www.tallinn.ee/est/geoportaal/Rakendused-2

- https://register.metsad.ee/#/

- https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/413042017008

- http://register.keskkonnainfo.ee/envreg/main?reg_kood=KLO5000024&mount=view#HTTPG3uSnPzNZWYDzqgNL2BtuBNxZ6BbUX

- https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

- Merimetsa kaitseala kaitsekorralduskava 2018-2027

- http://kunilaart.ee/en/artist/paul-burman/

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Paul_burman_Stroomi.jpg

- https://www.alamyimages.fr/photo-image-environs-de-tallinn-kaart-kava-lestonie-le-reval-ancienne-carte-antique-1912-baedeker-139060518.html

- "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tallinn"

- "https://www.tallinn.ee/eng/Stroomi-Beach-Park"

- "http://xgis.maaamet.ee/maps/XGis?app_id=UU82A&user_id=at&LANG=2&WIDTH=1236&HEIGHT=758&zlevel=4,538754.72378415,6588542.7055857&setlegend=SHYBR_ALUS01_82A=0,SHYBR_ALUS07_82AV=1"

- "https://dspace.emu.ee/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10492/4210/Kruus_Kertu_AR_mag_2018.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y"

- "https://content.sciendo.com/view/journals/fsmu/49/1/article-p59.xml"

- "https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/rms/0900001680080621"

- "https://www.coe.int/en/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/176/signatures"

Phase B: Landscape Evaluation and Assessment

B.1 Assessment Strategy

Based on our previous landscape system analysis we can see that Merimetsa/Stroomi coastal area is very unique because of its landscape diversity. There is a beach with a linear park, a forest and a swampy area. The area is very popular in Tallinn and also amongst tourists. That is also causing illegal wildfires and overall pollution. The area surrounding Merimetsa is very affordable right now considering how close it is to the sea and green area. That might change if the development pressure caused by the population increase in Tallinn will continue. That in turn might force the people living in the area right now to move. Therefore, the most important goals are to find the balance between nature preservation and human activity and prevent major changes from happening because of the social pressure.

Based on the previous information and analysis, it is important to map the following elements: ecological, social and recreational.

B.2 Mapping

Social strategy. Põhja-Tallinn is moderately populated district in Tallinn and is quite popular among young people. There are three types of buildings in Merimetsa/Stroomi coastal area - soviet era buildings, smaller apartment buildings and new residental buildings. The smaller apartment buildings are very similar to the ones in Kalamaja, which are very popular right now. That is also visible when looking at the Kalamaja property prices. That means that there is definitely some social pressure coming from Kalamaja. As we can see there is already a new residental area in front of Merimetsa. If the prices also increases in Merimetsa/Stroomi area, that could cause people living there right now to move. At the same time tourists put a lot of social pressure on the beach and forest. It is clear that people want to spend time there, which is indicated by what we saw during observation (e.g illegal fires). That means that there is a demand for green public spaces. There are also quite many kindergartens and schools in the area, so maybe there could be some educational purpose in the Merimetsa as well.

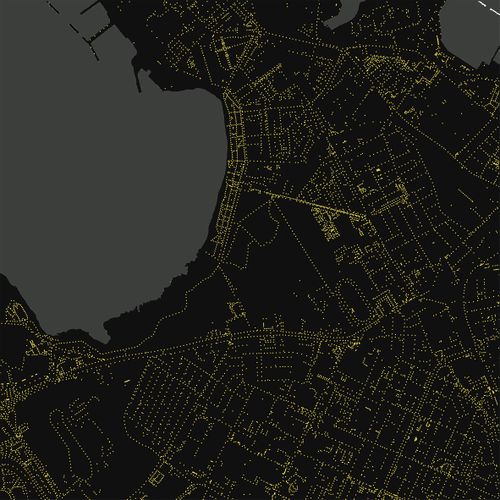

Protected Area This map defines all the different protected zones present in the area. The large amount of them and their location can be explained by the very natural aspect of the coastal line of Estonia which is an heritage of the USSR military border. However the area covered by each zone is still relatively small and sometimes does not really match the natural habitat of protected fauna species.

Anthropic pressure This map assesses the anthropic pressures undergoing around Merimetsa area for the ecosystem. We can see that some industries in the nearby area are potentially polluting the soil in a certain perimeter which could have disastrous consequences if these areas would come closer to Merimetsa. On the other hand, social pressure apply by nearby residential neighbourhood is also endangering the ecosystem: the more space is removed from the green area, the more its resilience will decrease.

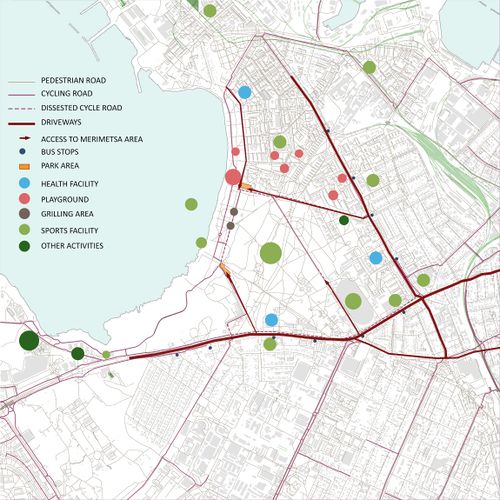

Recreational Assessment This map shows the services and infrastructures network in Merimetsa area. As for the communication routes, it is served by the Sole road from north to south, which connects the northern area of the district with the city center, and from east to west Paldiski road, which connects the area with the whole region. The area is also characterized by a bike path that is mostly damaged. As for accesses and points of reference, they are not clear and often not present. There are also few car parks, at the ends of the areas.

B.3 Problem definition and priority setting

Problems

- Rubbish pollution: Since the area is often very crowded, a lot of rubbish is left behind.

- Urbanisation: In case of further development of neighbouring residential areas the trees of the forest could be cut down and the property prices might rise a lot.

- Air pollution: Since the area is very popular, a lot of people want to go there. Right now there isn't a very good bike route that connects Merimetsa with surrounding areas. That means a lot of people might come with a car, which will cause air pollution.

- Soil & water pollution: There is a risk for impending pollution from the surrounding industry and the harbour.

- Forest Fire: Wild fires, that pose a great threat of forest fire during the summer months. Right now they are very common in the forest, because there isn't enough legal fireplaces.

Potentials

- Biodiversity: Merimetsa has a high potential for various natural functions and activities, which should be protected.

- Cultural heritage: The hippodrome could be very well integrated as an aspect of recreational.

- Accessability: In general the accessibility to area is well developed. The accesses to the watershore for prams and wheelchairs could be improved , maybe with a seafront.

- Fireplaces: Controlled fire through adequate and safe prepared fireplaces could be a good solution for the safety, recreational and the social aspects.

- Green infrastructure in bigger scale: Merimetsa area has the potential to connect the “green islands“ of Tallinn.

- Education: There are quite many schools/kindergartens near Merimetsa. Maybe Merimetsa could provide some educational value for them (e.g. educational trails).

Priorities

The priority in Merimetsa/Stroomi coastal area would be to keep the littering and damage of the nature as minimal as possible in a long term. Some steps have already been taken for that. For example, a better bike route connections have already been planned that include our area. Since there are many kindergartens/schools in the area, maybe there could be a educational trail in the area that would teach children to respect nature from the early age.

B.4 Theory reflection

The Strengths-Weaknesses-Opportunities-Threats (SWOT) analysis framework was used to evaluate Merimetsa-Stroomi competitive potentials and to develop strategic planning through evaluating internal and external factors.

By mapping different ecosystem services, it was easy to see the potentials of the area and also what was missing. We mostly focused on cultural and recreational services.

The Landscape Character Assessment helped us get an overview of the Merimetsa-Stroomi area in a wider context, namely the relation of the area to its surroundings and how the different types and uses of this coastal landscape interact, be it clashing or complementing. The focus area's distinctive combination of a thick vegetation cover and an overall maritime feeling is made more comprehensible by the Landscape Character Assessment.

We have encountered some limitations, however. We found it challenging to assess the forest landscape in a short timespan, which also happens to be at the very beginning of the vegetative season. Some maps are not up to date, making it rather difficult to understand the present situation at the focus area without consulting more recent data sources. Not being able to visit the area has also been a serious drawback during the initial stages.

B.5 References

- http://statistika.tallinn.ee/citizmap.php?bookmark=69ed7d632d44bc98ff88fb7b78057c0f&view_type=table&fbclid=IwAR3Ym1ICU2iluiXN_GsDx6vINkrH1ZLNVEUxATfi-BFPsJdlEMzs38b-duM

- https://www.tallinn.ee/est/Pohja-Tallinna-arengut-veavad-Kalamaja-ja-Pelgulinn

- https://www.manguvaljakud.tallinn.ee/

- https://transport.tallinn.ee/index.html#map/map,max

- https://gis.tallinn.ee/andmekorje/

- https://www.tallinn.ee/est/geoportaal/Rakendused-2

Phase C – Strategy and Master Plan

C.1 Goal Setting

Based on our finding that the natural character of the Merimetsa-Stroomi area is its most important value, we have decided on a minimum intervention approach. There is an opportunity to make use of the pollinator corridor and to establish a connection with other green areas in the vicinity. The intent behind this objective is to improve the city's microclimate and provide a more functional habitat for the wildlife.

Making the forest more people-friendly will ensure that the potential for recreation can be fully exploited, contributing to the health and well-being of the population of the surrounding neighbourhoods and the rest of the city. This, as well as the site's educational potential, will also lead to a greater appreciation of the forest and reduce the threat of losing it to real estate development. The hotspots of human activity should be developed in such a way that the visitor load does not threaten the site, which at present mainly happens through fire and soil degradation.

C.2 Spatial Strategy and Transect

- translate your strategic goals into a vision

- develop a spatial translation of your vision

- exemplify your vision in the form of a transect with concrete interventions

- add map(s) and visualizations

Masterplan. The main idea proposed is to create a educational trail through Merimetsa. Throughout the trail there will be different study areas where it will be possible to learn about plants, bugs, birds and fish. The trail will be partly on natural ground and partly on boardwalk, which makes it accessible for everyone.

C.3 From Theory of Change to Implementation

- For implementing your vision: Which partnerships are needed? Which governance model is required?

- Who needs to act and how? Draw and explain a change/process model/timeline

- Which resources are needed? On which assets can you build?

- add 150 words text and visuals

The implementation of our vision depends on a close partnership with policymakers, who have to be convinced that the landscape we envisioned would be appreciated by the population and function as a significant asset to the city in terms of the global climate crisis, the health and well-being of the citizens, and the overall quality of life. The intent is to give the space a greater value in the eyes of the people, who can then be expected to be emotionally invested in preserving it.

- Your case spatial your governance model.jpg

add caption here

- Your case spatial your process model.jpg

add caption here

C.4 References

- CORINR Land Cover. Copernicus. Retrieved 9 May 2019.

- Povilinskas, Ramunas (December 2002): Tallinn (Estonia). Restrieved 3 May 2019.

- https://www.tallinn.ee/putukas/

D. Process Reflection

The diversity of educational and national backgrounds of the eight members of the team made the study of this forest-dominated coastal landscape fun and enjoyable. Perhaps more importantly, this variety also provided plenty of opportunities for learning and understanding new perspectives. It was inspiring to share the knowledge of ecology, design, planning, sociology, and history among each other and with our tutors. The coastal landscape the majority of us are familiar with differs notably from the one we studied here, and the discussions and the comparisons helped us reach a vision while at the same time expanding our horizons.

Coming from several different countries and with a vast majority of us not speaking either of the languages common in the city of Tallinn, we found it somewhat difficult to gather information about the site and its surroundings from literature or through interviewing the locals. This was obviously a significant drawback, but it also served as an incentive to rely more on maps and on our own impressions of the site once we could finally explore it in person. A more efficient organization and time management on our part, mainly adjusting schedules, would have likely prevented some minor tensions and facilitated the course of the online portion of the study.